Post-exploitation tasks frequently require manual analysis, such as relying on an operators’ expertise to scan a target environment for sensitive information that could support in the pursuit of an objective. For example, searching file shares and internal applications for sensitive information of credentials. These tasks are often time consuming, but can be dramatically improved with the application of AI/ML.

This blog will discuss prior work in AI tooling and explore the requirements for AI/ML in post exploitation scenarios. Additionally, it will discuss key advancements in Windows AI/ML APIs that make it easy to integrate them into Cobalt Strike’s post-exploitation workflows. Lastly, this blog will also present two proof-of-concept implementations for AI-augmented post-exploitation capabilities in Cobalt Strike. The two proof-of-concept implementations can be found here.

Prior Research

Many current post-exploitation tools used for credential search, like Trufflehog, rely on regular expressions to scan for credential patterns in files. While effective in certain contexts, regex-based detection is inherently limited to known formats. This means unconventional or unformatted plaintext may be missed, leaving gaps in coverage that AI approaches are better positioned to address.

One notable example of prior work in weaponizing AI for post-exploitation tasks is SpecterOps’ DeepPass implementation. SpecterOps trained a Bi-directional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) model to identify passwords in downloaded documents. While the capability itself is compelling, it does have a significant limitation in that all documents of interest must first be identified and exfiltrated before classification can occur. These requirements increase operational risk in cases where documents are blindly downloaded in bulk and undermine the primary advantage of AI-driven automation when documents must be pre-filtered by operators.

In contrast, SharpML by AtlanDigital takes a more self-contained approach by embedding a machine learning inference directly into a single binary designed for on-target deployment. This implementation avoids reliance on external infrastructure but introduces its own limitations. During execution, SharpML writes three components to disk: the model, rule definitions, and password samples. This reliance on file-based artifacts makes it easily identifiable and therefore reduces its stealth and viability in real-world offensive workflows.

Post-Exploitation Considerations

Previously, the context in which a post exploitation task is typically performed has imposed operational restrictions around the use of AI/ML. This was because the available models and ML primitives used during preprocessing were not available from an in-memory context. Therefore, to maximize the utility of our AI-enabled tooling, dependencies must be minimized, and the development format should be compatible with in-memory execution.

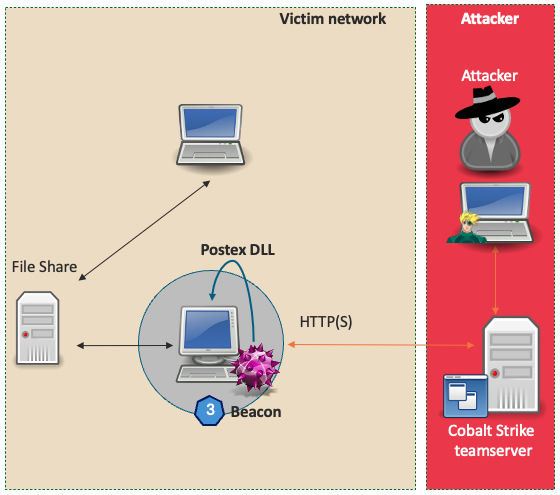

In Cobalt Strike 4.10 we introduced the postex-kit, a template that allows users to plug-in to Cobalt Strike’s existing job architecture to create long running postex jobs. Postex DLLs function by being reflectively loaded into either a sacrificial process or an explicit target process and communicate with Beacon through a named pipe. At development time, the postex-kit allows access to higher-level C++ programming practices that are normally unavailable in more primitive formats like BOFs. By making available these higher-level C++ features, the postex-kit reduces the effort required for data manipulations often needed in pre-processing steps. These attributes make the postex DLL format ideal for AI/ML post-exploitation capability development.

Advances in AI/ML Libraries

Since the release of Windows 10 version 1809 in October 2018, Microsoft has made AI/ML APIs available through the Windows ML framework. This framework is built on top of the ONNX Runtime, which is a platform agnostic library that allows for the use of models stored in the Open Neural Network Exchange (ONNX) format. The ONNX Runtime and the CPU and DirectML execution providers were initially designed for deploying machine learning models within Universal Windows Platform (UWP) applications. Although early support was limited to legacy ONNX opsets, Windows 11 version 21H2 (2104) introduced support for ONNX opset 12, significantly expanding model compatibility and functionality.

Importantly, these APIs are not limited to UWP applications; they can also be accessed from native C++ applications, enabling broader integration scenarios. This means that models trained using standard Python-based workflows can be exported to a supported ONNX format and seamlessly used in C++ code. When combined with the flexibility of the postex DLL template discussed earlier, these Windows ML APIs can be integrated into post-exploitation tooling, reflectively loaded with either the default or a user-defined postex reflective loader, and executed entirely in-memory. Through these interactions, the ability to access model inference (i.e. predictions or decisions) in a reflectively loaded context becomes available to users of Cobalt Strike.

Building a Local Credential Finder

The advances in the AI/ML ecosystem on Windows outlined in the previous section, along with the release of the postex-kit, have provided a powerful platform for the development of novel AI-augmented capabilities for offensive security professionals. By re-implementing SpecterOps’ DeepPass in a compatible format, a credential classification model can be embedded into a postex DLL and used to provide inference on candidate strings at run time. The process begins by loading the model from a byte array.

LearningModel LoadModel()

{

/* Ensure the COM apartment is initialized for this thread */

init_apartment();

/* Create an in - memory stream */

InMemoryRandomAccessStream memoryStream;

/* Create a DataWriter to write the raw bytes to the stream */

DataWriter writer(memoryStream);

writer.WriteBytes(array_view<const uint8_t>(modelBytes, modelBytes + sizeof(modelBytes)));

writer.StoreAsync().get(); // Ensure data is written to the stream

writer.FlushAsync().get();

/* Rewind the stream to the beginning */

memoryStream.Seek(0);

/* Create a stream reference from the in - memory stream */

RandomAccessStreamReference streamReference = RandomAccessStreamReference::CreateFromStream(memoryStream);

if (streamReference == nullptr) {

return nullptr;

}

/* Load the model from the stream reference */

LearningModel model = LoadModelFromStream(streamReference);

return model;

}

Performing any kind of recursive search, candidate strings can be extracted from documents on the target system, encoded using the encoding scheme used at training time, and then passed into the model for classification. In this example, this capability is largely implemented in a single function shown below.

float GetPasswordProbability(LearningModel deepPassModel, UCHAR* testString) {

/* check the test string pointer and correct length */

if (testString == NULL || strlen((char*)testString) < MIN_PASS_LENGTH || strlen((char*)testString) > MAX_PASS_LENGTH) {

return 0.0f;

}

/* Set model device to CPU for max compatability */

LearningModelDevice device = LearningModelDevice(LearningModelDeviceKind::Cpu);

/* Create Session and binding */

LearningModelSession session(deepPassModel, device);

LearningModelBinding binding(session);

/* Get encodings from test strings */

std::vector<int64_t> encodedInput = EncodeWord(std::string((char*)testString));

/* Allocate setup shape for input tensor */

std::vector<int64_t> shapeInput = { 1, (int64_t)encodedInput.size() };

/* Build input tensor from input shape and data */

TensorInt64Bit inputTensor = TensorInt64Bit::CreateFromIterable(shapeInput, encodedInput);

/* Bind required inputs to model's input features */

binding.Bind(deepPassModel.InputFeatures().GetAt(0).Name(), inputTensor);

/* Run the model on the inputs */

auto results = session.Evaluate(binding, L"\0"); // Second param is supposed to be optional per the docs, but this call will fail on Win 10 without *some* wchar* in there

/* Get the results as a vector */

auto resultsVector = results.Outputs().Lookup(deepPassModel.OutputFeatures().GetAt(0).Name()).as<TensorFloat>().GetAsVectorView();

/* deepPassModel returns only 1 output, a probability expressed as a float */

return resultsVector.GetAt(0);

}

Weaponizing Existing AI Models

Another approach that is viable with the Windows ML APIs is the use of existing models. One use case for this might be the implementation of natural language-based semantic search to identify high-value information on target systems. A requirement for implementing semantic search is access to an embedding model, such as bge-base-en-v1.5, to generate embedding vectors from input strings. An embedding vector generated in this way effectively contains a numerical representation of the input text’s context, which can then be used to calculate similarities between two strings.

Training a capable embedding model of adequate capability requires significant time and resources. Therefore, being able to access existing versions of these models is a valuable capability. Modern embedding models are complex and generally require access to ONNX opset compatibility greater than what is available via the Windows ML APIs. However, by implementing a tailored distillation and conversion process, it was possible to export the bge-base-en-v1.5 model into ONNX opset 12, which provides compatibility with Windows 11 version 21H2. An additional benefit to this distillation process is that it provides an opportunity to reduce the embedding model’s size from approximately 400 MBs to around 30 MBs.

A couple of additional considerations should be kept in mind when working with an embedding model. Unlike the tailored BiLSTM model used in the previous example, the additional complexity of embedding models necessarily means that their size will be significant. In fact, working with over 30 MBs in a byte array in Visual Studio resulted in broken features and an unusable development experience. To circumvent this and improve performance at runtime, a compression step was applied to the model. Then, Matt Ehrnschwender’s bin2coff.py script was used to make the model a linkable COFF object, accessible at link time via Visual Studio’s project settings. Resolution of both issues allowed for the implementation of the SemanticComparison function, as shown below.

extern "C" unsigned char model_onnx_smol_start[];

extern "C" unsigned char model_onnx_smol_end;

float SemanticComparison(LearningModel model, std::string string_1, std::string string_2){

/* Input batch */

std::vector<std::string> text_1 = {string_1};

std::vector<std::string> text_2 = {string_2};

/* Evaluate the model and get embeddings */

IVectorView<float> embeddings_1 = EvaluateModel(model, text_1);

IVectorView<float> embeddings_2 = EvaluateModel(model, text_2);

[ …snip…]

/* Return similarity of the embeddings */

return CalculateCosineSimilarity(embeddings_1, embeddings_2);

}

BOOL IntelligenceMain(PPOSTEX_DATA postexData){

[ …snip…]

/* Decompress model from buffer */

DecompressData(model_onnx_smol_start, model_size, &decompressed_model, &decompressed_size);

/* Load Model */

LearningModel model = LoadModelFromBuffer(decompressed_model, decompressed_size);

/* Recursive search for strings - perform SemanticComparison */

return SemanticSearchDirectoryContents(model, referenceSemanticString, threshold, filePath);

}

For more in-depth implementation details and ready-to-use binaries, review the code available in the repository.

Integrating AI Post-Exploitation

To further demonstrate the seamless integration of postex DLLs within the Cobalt Strike framework ai-postex.cna was implemented to register these capabilities as custom commands available from the Beacon console.

Considerations

The implemented examples in our repository have some important limitations that must be acknowledged. The necessary Windows ML APIs are only available on modern versions of Windows and the examples have only been tested on the latest version of Windows 11.

To reduce the size of the semantic search postex DLL, a distillation step was applied to the bge-base-en-v1.5 model resulting in reduced inference-time fidelity and accuracy. The BiLSTM model developed as a part of this research was trained on a relatively small set of 4 million ASCII passwords and words and therefore should be considered unreliable when examining strings outside of the ASCII range. During internal testing the model was observed to be biased towards capitalization, and hyphenated words, and biased against excessive symbols in candidate strings.

Both DLLs are implemented to leverage CPU computation for model inference, which means significant CPU spikes can be expected during use. These DLLs are intended to be proof-of-concept implementations and use in production environments is discouraged.

Closing Thoughts

While much of the recent attention around Artificial Intelligence has focused on its generative capabilities and offensive use in social engineering, this blog has demonstrated that AI/ML can also offer meaningful advances in the post-exploitation phase. By leveraging modern Windows ML APIs, ONNX model compatibility, and the Cobalt Strike postex-kit, it’s now possible to build fully in-memory, AI-augmented post-exploitation tooling. The proof-of-concept implementations, credentialFinder.dll, and semanticSearch.dll highlight two compelling use cases: high-confidence password classification and contextual semantic search directly on target systems. These implementations serve not only as demonstrations of technical feasibility but also introduce the potential of AI-augmented post-exploitation tools to the security conversation.